COARSE GRAIN CASE STUDY SUMMARY – Germany

Mainstreaming the value of nature protection in fiscal policy:

Assessing the role of ecological fiscal transfers in the German policy mix for biodiversity conservation and ecosystem service provision

Contact: Christoph Schröter-Schlaack, UFZ

Contents:

Abstract

Case study location and conservation characteristics

Current instruments in biodiversity conservation

New and potential economic instruments

Instrument interactions in the federal/national/state policy mix

Fine grain analysis

Fine grain case study site description

Economic instrument effectiveness

Economic instrument costs and benefits

Economic instrument equity and legitimacy

Institutional opportunities and constraints for economic instruments

Integrated policy mix assessments at fine grain assessment level

--------------------------------------------------------------------

This summary description focuses on the coarse grain analysis as represented by the German national case study report (Deliverable 7.2.1) applying to the territory of Germany. We address and model the integration of ecological indicators into intergovernmental fiscal transfers from the national to the state, i.e. Länder level in Germany, and assess the role of ecological fiscal transfers in the overall German policy mix. The fine grain analysis in Germany covers two major topics:

1)Building on the coarse grain report on ecological fiscal transfers, detailed fine grain studies on different aspects of integrating ecological indicators in the German fiscal transfer system are pursued such as the development of appropriate conservation indicators, the detailed discussion of ex ante scenario modelling results, or the legal and institutional options and constraints for introducing ecological fiscal transfers. A substantial part of the fine grain analysis related to EFT is already covered in the national case study report. Fine grain analysis on EFT will be continued, resulting mainly in journal publications that will be integrated in the upcoming fine grain report.

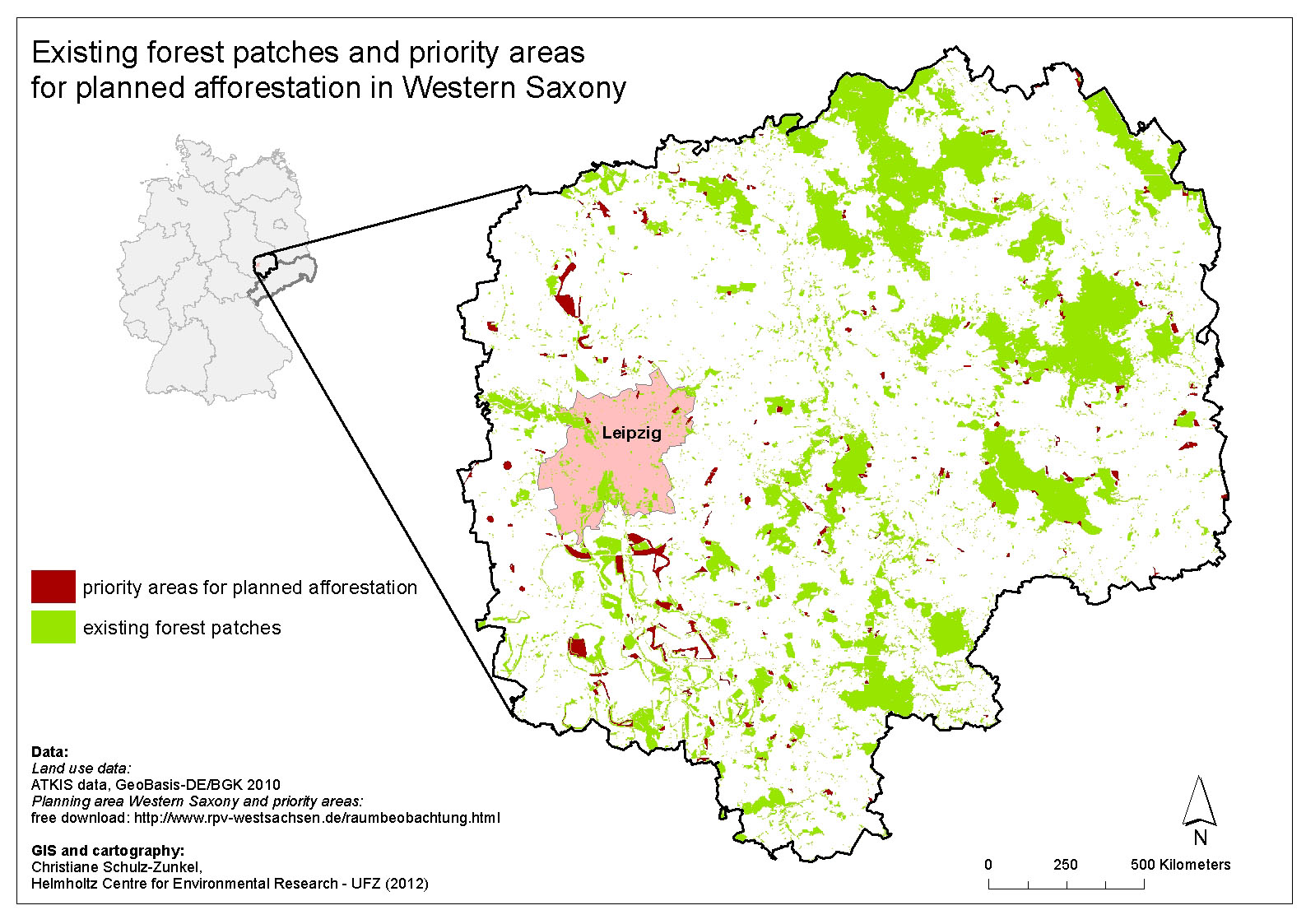

2) As Germany is a federal country with its states being responsible for implementing nature and forest conservation policies, a second major focus of the German fine grain analysis relates to the topic of afforestation and related ecosystem services in the Free State of Saxony. Here, the local level analysis investigates economic incentives for afforestation in Western Saxony and discusses the role of these instruments in the Saxon policy mix. This second topic will be a major focus of Deliverable 7.2.2 – Assessment of existing and proposed policy instruments for biodiversity conservation at state and local level.

The territory of Germany covers 357 021 km2 and is influenced by a temperate seasonal climate. With more than 80 million inhabitants it is the most populous member state of the European Union and amongst the most densely populated countries on a global comparison (Federal Ministry for the Environment, 2010a: 5). Agriculture is the dominant land use type (~52%). Though increasing in recent years, forest cover in Germany (~31%) is substantially lower than European average (~45%) (Federal Statistical Office Germany, 2012).

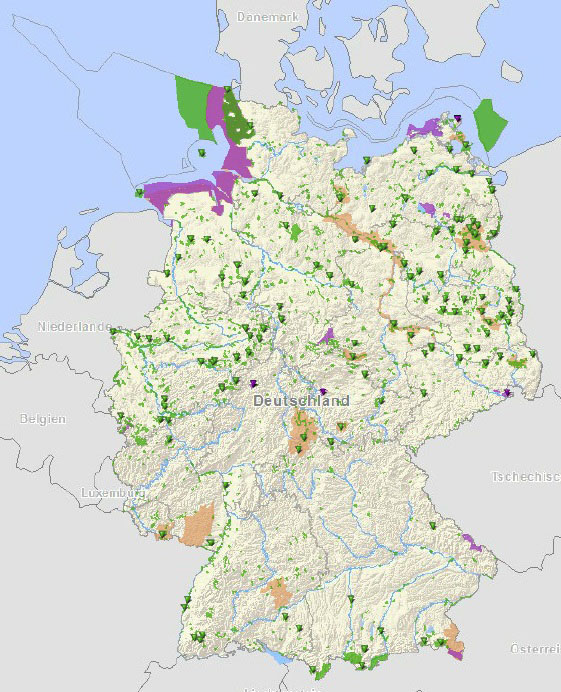

Conserving biodiversity is among the central elements of Germany’s National Sustainability Strategy adopted in 2002 (Bundesregierung, 2002). In 2007 Germany also adapted a National Strategy on Biological Diversity (Federal Ministry for the Environment, 2007). The Biodiversity Strategy contains 16 indicators for monitoring current status and trend of biological diversity, roughly 330 objectives with timeframes and about 430 measures calling the various governmental and non-governmental actors to action. There are five main goals of the strategy, namely (1) biodiversity conservation, (2) its sustainable use, (3) reducing environmental pollution, (4) conservation as well as access and equitable sharing of benefits of genetic resources, and (5) raising social awareness for biodiversity conservation as one of the top priorities for society. From an instrument perspective it is interesting to note that the strategy places strong emphasis on regulatory instruments, i.e. protected areas (Fig. 1) like national parks, biosphere reserves, nature conservation areas or Natura 2000 and interlinkage between critical biotopes, and the well-functioning management of these sites and corridors.

Conserving biodiversity is among the central elements of Germany’s National Sustainability Strategy adopted in 2002 (Bundesregierung, 2002). In 2007 Germany also adapted a National Strategy on Biological Diversity (Federal Ministry for the Environment, 2007). The Biodiversity Strategy contains 16 indicators for monitoring current status and trend of biological diversity, roughly 330 objectives with timeframes and about 430 measures calling the various governmental and non-governmental actors to action. There are five main goals of the strategy, namely (1) biodiversity conservation, (2) its sustainable use, (3) reducing environmental pollution, (4) conservation as well as access and equitable sharing of benefits of genetic resources, and (5) raising social awareness for biodiversity conservation as one of the top priorities for society. From an instrument perspective it is interesting to note that the strategy places strong emphasis on regulatory instruments, i.e. protected areas (Fig. 1) like national parks, biosphere reserves, nature conservation areas or Natura 2000 and interlinkage between critical biotopes, and the well-functioning management of these sites and corridors.

Figure 1: Figure 1: National Parks (purple), Biosphere reserves (orange) and nature conservation areas (green) in Germany. Source: Federal Agency for Nature Conservation (2012e).

For a more detailed view: German Agency for Nature Conservation

Another major focus is on stimulating sustainable use of ecosystems, i.e. cultivated landscapes used for agriculture and forestry, with a particular focus on the provision of habitats critical for the survival of endangered species or species for which Germany has a particular conservation responsibility. Against this background, the German POLICYMIX case study can be seen as an effort to support the aims of the Strategy on Biological Diversity and to facilitate the national TEEB-process by contributing to a better understanding of the interaction of policy instruments for biodiversity conservation with a particular emphasis on the role of economic instruments.

Nature conservation has a long tradition in Germany dating back to the first half of the 19th century (Aßmann and Härdtle 2002). The most important legislative outputs at federal level are the Federal Species Conservation Act (Bundesartenschutzverordnung – BArtSchV), and the Federal Nature Conservation Act (Bundesnaturschutzgesetz – BNatSchG) firstly adopted in 1976 but recently reformed and in effect since March 2010 (Table 1). The new legislation intends to harmonise nature conservation laws nationwide. The objectives in the new Federal Act on Nature Conservation and Landscape Management are determined by three main aspects, 1) conserving biodiversity, 2) enhancing productivity and functionality of the ecosystem, and 3) safeguarding variety, singularity, beauty and recreational value of nature and landscapes.

The main regulatory instrument for nature conservation is the designation and management of protected areas. Several types of protected areas are defined by Germany's Federal Nature Conservation Act and are designated by land-use planning at Länder level. They can be classified by size, protection purpose and conservation objective, and by the resulting restrictions on land use. The main types are nature conservation areas, national parks, biosphere reserves, Natura 2000-sites, landscape protection areas and nature parks.

Though since the end of the 1980’s the variety and funds related to incentive-based instruments for nature conservation are growing, they are still of minor importance compared to the impact of regulatory instruments. A few of these financial support programmes are issued at the national level, e.g. Testing and Development Projects in Nature Conservation and Landscape Management are funded by the German Ministry for the Environment, as is the direct financial support for important large-scale nature conservation and riparian zone projects by the federal government.

Starting with the EU agricultural reform in 1992, environment-related subsidies for agriculture have been systematically expanded and developed into the current agro-environmental measures as part of the policy for developing agriculture and rural areas. By converting the former production- and product-related subsidies for farmers in Germany into land-related subsidies and linking these payments to compliance with defined environmental protection (cross compliance), incentives for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity have been significantly enhanced. In Germany, these support programmes are implemented at the Länder level and mostly co-financed by the EU. Relating to our local level case study, the two most important incentive-based instruments for forest conservation in Saxony are 1) an agro-environmental scheme that supports afforestation on agricultural land and on other post-industrial sites, and 2) the Directive for Woodland and Forestry in Saxony that aims to increase forest conversion and supports forest-owners that take respective measures.

Table 1: Current (black) and new (blue) instruments for biodiversity and forest conservation in Germany, addressing various actors at different levels of government.

|

Actors addressed

|

Regulatory Instruments

|

Incentive-based approaches

|

|

Public

|

Federal

|

· Federal Nature Conservation Act

· Federal Species ConservationAct

· Federal Forest Conservation Act

|

|

|

Länder

|

· State Nature Conservation Act

· State Forest Act

· State and Regional Development

Plans

· Landscape Planning

· Offsets

|

· Life+

· Testing and Development projects

in nature conservation

· Funding for large-scale nature

conservation areas

· Ecological Fiscal Transfers at

Länder level

|

|

Municipalities

|

· Local land-use planning

· Green area planning

· Offsets

|

· Conservation support programmes

· Conservation support programmes

· Ecological Fiscal Transfers at

municipal level

|

|

Private

|

· Federal Nature Conservation Act

and Federal Species Conservation

Act

· Local land-use planning

· Offsets

|

· Agri-environmental schemes

· Conservation support programmes

· Directive for Woodland and

Forestry in Saxony

|

Although the instrument box for biodiversity conservation seems to be well equipped (see Table 1), sufficient funding of nature conservation activities is still lacking and drivers of biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation are persistent and often further spurred by other sectoral policies. This holds true for private conservation activities, e.g. by farmers or foresters but even more so for public policy makers in charge of landscape and conservation planning. Hence, the German case study looks at two promising instruments to complement the policy mix for biodiversity and forest conservation. Firstly, we explore from an ex ante-perspective the potential of integrating ecological indicators in intergovernmental fiscal transfers at federal level in Germany; and secondly, we study in depth the conditions for incentivizing farmers by PES for afforestation to contribute to the state’s aim of increasing forest cover in Saxony, a German state with a particularly low share of forest on total land cover.

Despite advances in implementing instruments that reward conservation at the private level in Germany (e.g., PES to landowners), there are few instruments addressing public actors. This might lead to an under-provision of the public good biodiversity conservation, since in such context subnational governments do not have incentives to take conservation benefits into account, especially those affecting other jurisdictions beyond their own boundaries. Ecological fiscal transfer (EFT) is an instrument that has potential to address this issue by distributing money from higher to lower levels of government based on ecological indicators. So far, only Brazil, Portugal and to a certain extent France have adopted EFTs (Ring et al. 2011a). While EFT is an innovative approach to German federalism, fiscal equalisation as such is not.

There is an extensive field of regulation covering the relationship between federal level, states (so-called Länder) and municipalities. The constitutional rules for the distribution of legislative power and responsibilities among these governmental levels are mirrored by a complex mechanism of distributing public revenues in order to provide governments with the funds necessary to fulfil their responsibilities.

Against this background, one set of questions tackled by the POLICYMIX project is whether it is suitable to integrate ecological indicators into the existing fiscal transfer system to account for the different levels of conservation activities by the Länder. What should an indicator for measuring the different levels of conservation activities look like? What are the legal options and constraints such an approach would face? How would this kind of incentive mechanism interact with other types of regulation concerning nature conservation? In defining potential indicators, we build on existing experience with EFT in Brazil and Portugal, and develop a series of protected area-based indicators for integration into the fiscal transfer system.

EFT build on existing protected area regulation in that they use officially designated protected areas as an indicator to allocate fiscal transfers. Hence, they synergistically complement conservation law with an economic incentive that accounts for state conservation costs and spillover benefits related to these protected areas (Ring et al., 2011a: 115). Depending on the indicators chosen, EFT may also facilitate indirect conservation measures such as avoiding further fragmentation of landscapes by traffic infrastructure development or patchy settlement expansion. Furthermore, EFT may provide the funds necessary to equip support programmes for conservation activities by private land users. From an institutional perspective it is also important to note that implementing EFT at state level may also provide an impetus for introducing ecological indicators at other levels of intergovernmental transfers, e.g. fiscal equalisation at municipal level, thereby boosting impacts resulting from EFT at state level.

Fine grain analysis –

Research questions and challenges for biodiversity and forest conservation

As outlined before, the fine grain analysis in Germany covers two different levels and instruments:

1) Ecological fiscal transfers at state level in Germany

Ecological Fiscal Transfers share some characteristics with payments for ecosystem services (PES) as they incentivize decision-makers to change their behavior in an environmentally friendly way. However, it is important to note, that fiscal transfers are first and foremost a distributive instruments, i.e. aiming at leveling off differences in the available public budgets per capita at the respective governmental levels. Hence, when ecological indicators are introduced without increasing the overall amount of money available to distribute, there will always be winners and losers and thus some states will receive less with EFT than under the status quo. Thus, effectiveness and efficiency of EFT for biodiversity conservation cannot be evaluated in rigorous way. The main research questions tackled by the fine grain analysis regarding EFT focus on 1) the creation of sound ecological indicators capable of representing the differences in conservation activities among the states, 2) options for their integration into the existing fiscal transfer scheme, and 3) simulation of EFT as proposed to showcase potential distribution results as an input for further discussion with stakeholders about the potential role of EFT in the conservation policy mix.

2) Agri-environmental incentive scheme for afforestation in Saxony

In Saxony, we focus on a new design of the agri-environmental scheme for forest increase. It has been found that this scheme in its current design is not attractive. This is due to very low compensation payments, partial reimbursement of investment costs and complicated application procedures. The current programme period is from 2007-2013. Authorities are now looking for ways to improve the scheme in the next programme period.

We investigate the terms and conditions under which landowners would be more interested to engage in the agri-environmental scheme for forest increase. These include economic issues (i.e. compensation payments, reversibility to agricultural use, contract length, competition of afforestation with other land uses), social /institutional issues (i.e. degree of administrative effort, consultation) and ecological issues (farmer’s interest in certain ecosystem services of forests, such as recreation, timber production, biodiversity). One possible reason for the limited interest of farmers in the agro-environmental scheme for forest increase is that agricultural production is more attractive. Since many farmers already participate in other agro-environmental programmes or conservation schemes, it might be possible that they are reluctant to change to yet another PES scheme. These terms and conditions will be investigated in a local case study area, namely Western Saxony (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Western Saxony - Case study area for local level fine grain analysis in Germany

1) Ecological fiscal transfers at state level in Germany

For the fine grain analysis of Ecological Fiscal Transfers, the site descriptions relating to Germany have already been presented earlier.

2) Agri-environmental incentive scheme for afforestation in Saxony

In the Saxon fine-grain analysis the relevant ecosystem services are not related to existing forests but to new forests that will be grown on agricultural land in accordance with the agro-environmental scheme for forest increase. We look at the importance landowners in Western Saxony place on different ecosystem services and biodiversity aspects and investigate how these affect the decision to participate in the afforestation scheme. The ecosystem services include future recreational use and timber production. In terms of biodiversity, we ask for landowners’ preferences for production forest (1 or 2 species, little diversity) and natural forest (several species, high diversity). Ecosystem services associated with new forests are identical in the Dutch case study, possibly Barrancos and further POLICYMIX case studies.

1) Ecological fiscal transfers at state level in Germany

Ecological Fiscal Transfers aim at public actors and provide incentives to public actors. If protected areas/area-related conservation indicators are integrated into intergovernmental fiscal relations, there is a spatially explicit consideration of these conservation areas in terms of increasing the fiscal needs of the relevant state government. Thus, existing protected areas are considered in a spatially explicit way – although potentially weighted according to conservation value and land-use restrictions associated with them. This might have two effects on conservation efforts: Länder could designate new protected areas, and Länder could redesignate their existing protected areas to stricter protection categories to receive a higher weighting factor. However, the incentive effect for future conservation is not spatially explicit. In this way, it is not possible to evaluate the ecological effectiveness of EFT in a rigorous way. Regarding competing land uses at state or municipal levels, EFT will most probably change land-use patterns in the long term as on average protected areas are valued higher and do provide monetary benefits to state or municipal budgets. Depending on the ecological indicator chosen, one may evaluate the change of this indicator in the long run.

2) Agri-environmental incentive scheme for afforestation in Saxony

With respect to the agro-environmental scheme for forest increase, we would like to compare the scheme with 1) other instruments for forest increase (mainly foundations) and 2) other competing instruments of relevance to farmers (i.e. premium for set aside land is more attractive). The most restricting factor in analysing cost-effectiveness is little knowledge about the transaction costs of the different instruments. In a questionnaire with farmers we will elicit the payments farmers receive for other conservation measures.

1) Ecological fiscal transfers at state level in Germany

As mentioned above, the distributive aim of fiscal transfers makes it hardly impossible to rigorously assess the costs and benefits associated with integrating ecological indicators. Nevertheless, some qualitative judgements can be made. Firstly, by acknowledging conservation efforts as a public responsibility eligible for fiscal transfers, public actors are incentivized to rethink their long-term development strategies that are nowadays singularly focused on tax-creating land uses. Thereby a gap in the conservation policy mix is closed, as fiscal transfers address public decision makers that in turn create the framework for decisions by private land users, e.g. by land-use and land-development planning. Secondly, transaction costs of EFT will be moderately low, since all necessary regulation for intergovernmental fiscal transfers is in place, ecological indicators chosen are mostly based on available data and only the basis for calculating size and direction of transfers is modified.

2) Agri-environmental incentive scheme for afforestation in Saxony

With respect to the agri-environmental scheme, we use a Choice Experiment and a follow-up questionnaire to investigate compensation required by landowners for converting some of their land into forest.

1) Ecological fiscal transfers at state level in Germany

On the one hand, EFT can provide a counterbalance in relation to existing, often adverse incentives for land use, such as attracting more inhabitants and businesses, agricultural land uses, settlements, construction and housing. On the other hand, intergovernmental fiscal transfers are not primarily targeted towards biodiversity conservation but strive towards levelling off substantial differences in available tax revenues per capita. In this way, fiscal transfers are per se a redistributive instrument, accounting for fiscal needs in relation to the fiscal capacities of relevant jurisdictions. Financial constitutions (in Germany part of the Basic Law) and fiscal transfer laws thus represent the result of a complex bargaining process between the federal level and the states of what is considered fair and legitimate in a certain period of time. As these laws are always a result of political majorities, bargaining continues for law changes, especially of those states that pay more than they receive. If ecological indicators are newly integrated, the relative weight of other criteria in the distribution formulas is reduced that is mainly the number of inhabitants. As the number of inhabitants is the agreed abstract indicator for representing fiscal needs of various inhabitant-related public functions, e.g. infrastructure needs for housing and transport, social security and health care, education and cultural activities, loosing states with an EFT scheme will also have less money for these other public functions. However, beside some qualitative judgements it is way beyond the scope of the POLICYMIX fine grain study to assess the welfare effects of this shift.

2) Agri-environmental incentive scheme for afforestation in Saxony

With respect to the agri-environmental scheme for forest increase we have included questions regarding the social impact of the scheme in the Choice Experiment. We plan to conduct qualitative interviews with farmers who refuse to participate in the afforestation scheme in the Choice Experiment to determine the reasons why they do not want to participate and the extent to which shortcomings in the implementation of the instrument play a role. This allows us to filter out possible social impacts and distributional fairness issues (i.e. is a certain group disadvantaged: part-time vs. full-time farmers, high soil fertility rate vs. low soil fertility rate, size of landholding).

1) Ecological fiscal transfers at state level in Germany

There are several options to integrate ecological indicators into the German fiscal transfer system at state level. We choose to integrate a conservation factor at the stage of horizontal equalisation, i.e. where fiscal needs and fiscal capacities of the states are compared and levelled off. This is due to the fact that already now, higher fiscal needs of states with very low population densities (which can be understood as an area-related indicator) are considered at this particular stage. In this way, conservation efforts are “translated” into additional inhabitants and thereby into higher fiscal needs. Another option would be to put conservation-related indicators side by side to population-based indicators. Moreover, as our preliminary simulation has shown, marine protected areas should be considered in a separate form. As our chosen indicator relates the protected area of a state to its overall area, the large size of marine protected areas in relation to the land size of the relevant states (such as Schleswig-Holstein) highly distorts the results. Furthermore, marine protected areas are associated with considerably different opportunity and management costs than their terrestrial counterparts, leading to a strong bias in favour of coastal states.

2) Agri-environmental incentive scheme for afforestation in Saxony

With respect to the agri-environmental scheme for forest increase, we have conducted a number of in-depth interviews with a variety of forestry authorities. According to these interviews, the main institutional constraints are related to the complicated application procedure and administrative effort, to the lack of personnel to promote the scheme and to assist farmers during the application process, and to the fact that the scheme is voluntary.

1) Ecological fiscal transfers at state level in Germany

As ecological fiscal transfers are introduced at the national / state level, please see section on “Instrument interactions in the federal/national/state policy mix” above.

2) Agri-environmental incentive scheme for afforestation in Saxony

In the local fine grain analysis, conclusions will be derived regarding the agri-environmental incentive scheme for afforestation in Saxony, whether the instruments acceptance by farmers and thus effectiveness in terms of forest increase can be enhanced through design changes. This will be discussed in the light of its co-existence with other existing instruments, such as foundation’s activities for forest increase, and other agri-environmental measures possibly competing with the afforestation scheme.